Transcatheter Aortic Valve (TAVR) One-Year Outcomes Reported

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) was approved by the FDA in 2011 as a method of alleviating aortic stenosis in patients too frail to undergo open heart surgery. This week, the Journal of the American Medical Assocation (JAMA) published a comprehensive study of TAVR patient one-year outcomes that included information on mortality, stroke, and rehospitalization.

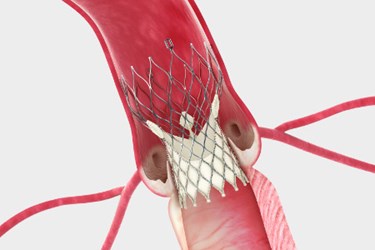

The Mayo Clinic reports that nearly one third of aortic stenosis patients are not candidates for open heart surgery due to complications such as age or comorbid conditions. TAVR, in comparison, is a minimally invasive procedure in which doctors access the aorta through a blood vessel in the leg. The replacement valve is guided into place using a catheter.

“TAVR has become transformational for patients who need a new valve and are at high-risk for surgery or inoperable. But we have been lacking long-term data for this group of patients who are considering this procedure,” David Holmes, a Mayo Clinic interventional cardiologist and lead author of the JAMA study, said in a press release.

The researchers gather information by linking data from the Transcatheter Valve Therapies Registry, a centralized information collection system developed by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the American College of Cardiology, with Medicare/Medicaid Services administrative claims. In total, the study included 299 hospitals and 12,182 patient swho had undergone the procedure between 2011 and 2013.

According to a JAMA study, “Among patients undergoing TAVR in U.S. clinical practice, at 1-year follow-up, overall mortality was 23.7 percent, the stroke rate was 4.1 percent, and the rate of the composite outcome of death and stroke was 26 percent.”

Of the 12,182 patients in the study, the median age was 84 years. Four percent of patients were rehospitalized once, and 12.5 percent were rehospitalized twice. Seven percent of patients died within 30 days of the procedure, and almost 24 percent died within one year.

The study authors wrote that the data might be particularly helpful to doctors hoping to identify which patients are particularly unsuitable for the procedure and advise those patients accordingly.

“Before this study, we only had 30-day information. This is a milestone and will help us better guide patients and learn as physicians,” said Holmes.

In an interview with Forbes, Ajay Kirtane, interventional cardiologist at Columbia University, pointed out that candidates for current TAVR indications are among the most critically ill cardiovascular patients that cardiologists encounter, and it is important to remember that when analyzing these numbers.

“I agree with the authors that this emphasizes the need for tools to predict more accurately which patients are chronically ill with aortic stenosis versus those who are ill because of aortic stenosis. The latter would appear to be the best candidates for TAVR, while the former would likely not be,” said Kirtane.

Over the past several years, Medtronic and Edwards Lifesciences have introduced transcatheter replacement valves to the U.S. market, and numerous other companies have TAVR devices in development, including St. Jude and Boston Scientific. (Med Device Online profiled a startup company’s development of a new TAVR approach in the article Reverse Engineering A Human Heart Valve.)

Sanjay Kaul, interventional cardiologist at Cedars-Sinai, told Forbes that the study “highlights the critical importance of patient selection in optimizing the benefit-risk balance of this important technology.”

“It is reassuring to witness this commitment to prudent and responsible dissemination of this technology by the stakeholders,” Kaul added.

Image credit: CoreValve in situ by Medtronic