Total Productive Maintenance, Part 2: Autonomous Maintenance

By Darren Dolcemascolo, senior partner and co-founder, EMS Consulting Group

Over the last few editions of Thinking Lean we have been talking about tools that support continuous flow and pull systems. In the last edition, we began a two-part series on total productive maintenance (TPM). In this edition, we will talk about autonomous maintenance.

Autonomous Maintenance Program

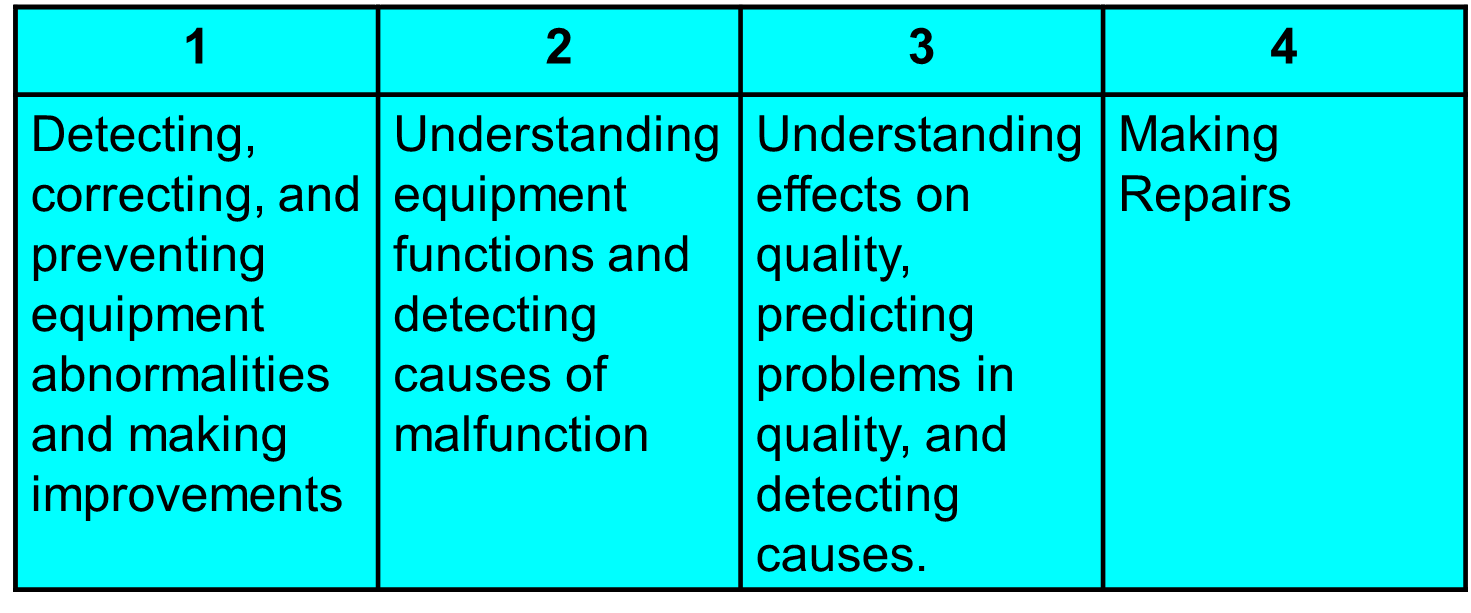

An autonomous maintenance program stabilizes equipment and halts accelerated deterioration. The program makes operators responsible for cleaning and inspection, lubrication, precision checks, and other light maintenance tasks. In carrying out these activities, operators learn more about their equipment and become better equipped to detect problems early. To implement such autonomous maintenance, operators are systematically trained. There are four levels of skill that operators may attain, depending on the organization’s needs and types of equipment:

The steps to implementing autonomous maintenance include:

- Initial cleaning

- Countermeasures to sources of contamination

- Cleaning and lubricating standards

- Overall inspection

- Autonomous maintenance standards

- Process quality assurance

- Autonomous supervision

Initial cleaning is the first step of autonomous maintenance; it is analogous to the “shine” component of 5S. Cleaning equipment reveals defects like cracks, poor lubrication, or other malfunctioning parts. Cleaning equipment is important because debris in mechanical, hydraulic, or electrical systems can lead to malfunctions, wear, and loss of precision. Contamination on equipment can lead to contaminated, defective product. For example, dirt on fixtures or tools in a precision machine tool can cause eccentricity during machining, and result in defective parts.

Implementing countermeasures to sources of contamination means controlling the sources of debris. This is done by repairing leaky pipe joints, installing shields where necessary, and making other repairs and modifications to eliminate the source of debris and keep equipment functioning properly. It also means modifying equipment to make cleaning and inspection easier. For example, installing a window where there was not one previously might make inspection quicker.

Implementing cleaning and lubricating standards can be accomplished by using the information gained from the previous two steps: identify optimal cleaning and lubrication conditions for the equipment, and develop standards to maintain them. This includes specifying the lubricant to be used and limiting the number of lubricants to the minimum; listing and diagramming all lubrication inlets on each machine; improving the lubrication system in centrally lubricated equipment and diagramming the route from pump to main pipes, branch valves, branch pipes, and lubrication points; tracking and measuring usage of different lubricants; and specifying proper disposal procedures.

Under TPM, cleaning and lubrication standards are more likely to work because operators are involved in maintenance, equipment is improved to make access easier, and time required for cleaning and lubrication is included in the daily 5S cleanups.

Overall inspection further improves operator skill level and standardizes inspection procedures. The goal is for operators to become better at identifying abnormalities so that the number of breakdowns will decrease. In order to do this effectively, operators must first receive training in equipment subsystems, such as lubrication, pneumatics, hydraulics, electrical circuits, drive systems, and fire prevention.

The maintenance group’s workload should have been reduced because of steps one through three. This freed-up time should be used to develop operator training materials and visual aids, such as instruction sheets / standard work charts, diagrams, models, or any other training aids deemed necessary. The training itself must be hands-on, at the equipment, to be effective.

To aid inspection, visual aids should be used. The aids should make it easy to understand what needs to be checked, communicate the function and structure of each equipment part, make it easy to tell whether the condition being checked is normal, and communicate what action should be taken if an abnormal condition exists. Examples of visual aids that will aid operators in inspection and maintenance include gauges, color-coded electrical and mechanical connections, tags and labels that indicate inspection or lubrication points, and match marks that aid in bolt placement.

Autonomous maintenance standards address five key areas. First, review standards and documentation for cleanliness, inspection, and lubrication. Next, consult with the maintenance department about inspection points. Be clear and specific about job assignments to avoid omissions. Use visual controls (charts) for job assignments, very similar to what you would do with the “standardize” step of 5S. Determine whether enough time is allocated for inspection tasks; if not, look for time-saving improvements.

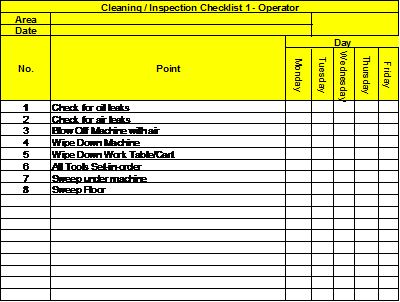

Fourth, determine what additional skill upgrades are necessary for continuous improvement of the TPM program. Finally, implement audits to ensure that autonomous inspection is carried out correctly by all operators. Below is an example of a checklist that may be used as part of 5S and autonomous maintenance.

Process quality assurance focuses on the relationship between equipment conditions and the quality of the product being produced. Engineering, maintenance, and operators must work together for this step to be successful. Operators need to learn how to relate product defects to equipment performance, and identify opportunities to implement controls that prevent or detect errors. Generally, the best way to do this is through mistake-proofing: putting in place sensors or passive devices that detect abnormalities, and then either stop the machine or signal operators/inspectors using an audible and visual signal.

Autonomous supervision is analogous to the “sustain” step of 5S. We use regular auditing to ensure that standards are followed and reward systems to re-enforce the discipline. Finally, we tie TPM and its metrics to performance reviews / provide incentive to sustain and improve.

Each element of TPM is important for a lean medical device manufacturer. Improving availability, performance, and quality on equipment will improve flow, reduce inventory, and provide a competitive advantage.