Spectrometer "Sniffs" Feces For Rapid Bacteria Detection

By Chuck Seegert, Ph.D.

Using an electronic nose (fortunately), University of Leicester researchers have developed a way to “sniff” a patient’s feces, enabling the identification of certain strains of the problematic bacteria Clostridium. This test is more sensitive than others and with development may be the fastest.

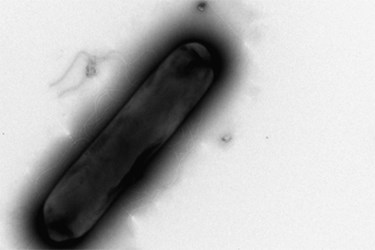

Clostridium difficile (C-diff) is a highly infectious bacteria that causes diarrhea, cramps, and even elevated temperatures. It is a problem in hospitals that can lead to increased length of stay and treatments that may complicate original disease conditions. Unfortunately, proper treatment relies on evaluating strain information, which is currently difficult.

“Current tests for C. difficile don’t generally give strain information,” said Dr. Martha Clokie of the University’s department of infection, immunity, and inflammation, in a recent press release. “This test could allow doctors to see what strain was causing the illness and allow doctors to tailor their treatment.”

Using a mass spectrometer, it possible to “sniff” the strain of the infecting bacteria by detecting characteristic volatile organic compounds (VOCs) that each strain releases.

According to the press release, the work was a collaboration between chemists at the university, along with the microbiology department, which maintains an extensive collection of well-studied strains of C-diff. The collection was used to demonstrate that different strains of bacteria have unique “smells” to the mass spectrometer.

Results of the team’s research were published in a study in Metabolomics. Their work focused on 10 strains of the C-diff bacteria that were closely examined for 69 VOCs. Each of the ten strains exhibited a specific balance of VOCs that can be used to identify them.

“Our approach may lead to a rapid clinical diagnostic test based on the VOCs released from fecal samples of patients infected with C. difficile. We do not underestimate the challenges in sampling and attributing C. difficile VOCs from fecal samples,” said professor Paul Monks from the University’s department of chemistry in the press release.

Knowing the specific strain can help decision making in the treatment of patients.

“Delayed treatment and inappropriate antibiotics not only cause high morbidity and mortality, but also add costs to the healthcare system through lost bed days. Different strains of C. difficile can cause different symptoms and may need to be treated differently so a test that could determine not only an infection, but what type of infection could lead to new treatment options,” said professor Monks.

The team hopes to turn the mass spectrometry test into a clinical assay.

“This work shows great promise. The different strains of C-diff have significantly different chemical fingerprints and with further research we would hope to be able to develop a reliable and almost instantaneous tool for detecting a specific strain, even if present in very small quantities,” said professor Andy Ellis from the University’s department of chemistry in the press release.

Preventing the spread of C-diff in hospitals is a relevant problem that is receiving elevated levels of attention. In an article recently published by Medical Device Online, ultraviolet cleaning was used as part of an effort to reduce the effects of C-diff and other bacteria in hospitals.

Image Credit: University of Leicester