Novel "Biospleen" Selectively Cleans Pathogens From Blood

By Chuck Seegert, Ph.D.

Sepsis, or a severe systemic reaction to infection, has historically been extremely difficult to treat. Instead of using large doses of general types of antibiotics, healthcare providers may now have another option called a “biospleen.” This device selectively and efficiently cleanses bacteria and other pathogens from the blood, without damaging the blood itself.

As infection levels increase in the body, its natural defense mechanisms can be overwhelmed. When this happens, the infection can invade the blood and cause sepsis, a whole-body inflammatory reaction that is often fatal. Attempts to treat infections causing sepsis can be hampered by a lack of understanding about where the infection originated. Sometimes large doses of antibiotics are used in an attempt to knock the infection down to a level that the body handle. Unfortunately, because of the speed that sepsis can move, it may not be helpful even if antibiotics are administered.

A general way of cleansing the blood without knowing what is infecting it would be an ideal solution in these situations, and that is what Harvard researchers have been developing, according to a recent press release.

"Even with the best current treatments, sepsis patients are dying in intensive care units at least 30 percent of the time," said Mike Super, Ph.D., a senior staff scientist at Harvard’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering, in the press release. "We need a new approach."

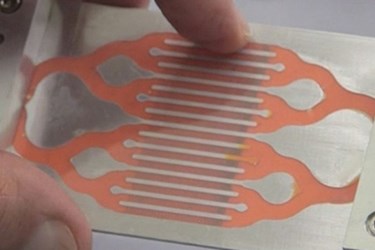

The device has been called a biospleen, and it can effectively cleanse bacteria or viruses that are either dead or alive, as well as the byproducts these pathogens can create. According to a study published by the team in Nature Medicine, the device uses magnetic nanoparticles that are mixed with the blood. On the surface of the nanoparticles are bioactive molecules called mannose binding lectin, a human opsonin that attaches to many pathogens and toxins. The nanoparticles, after having time to attach, are then drawn from the blood using a magnet, leaving the cleansed blood to be recirculated into the patient.

Using a rat model of sepsis in the study, the team was able to show that 90 percent of the rats were alive after treatment with the device, whereas the control group had only a 14 percent survival rate.

"Sepsis is a major medical threat, which is increasing because of antibiotic resistance. We're excited by the biospleen because it potentially provides a way to treat patients quickly without having to wait days to identify the source of infection, and it works equally well with antibiotic-resistant organisms," said Wyss Institute founding director Don Ingber, M.D., Ph.D., in the press release. "We hope to move this towards human testing to advancing to large animal studies as quickly as possible."

Filtering pathogens from blood is an area of biomedical research that a number of teams are focusing on. Recently, a team at Oregon State University was awarded a significant NSF grant to develop a similar filtration method. Their device uses microfluidic channels to capture the bacteria and pathogenic byproducts.

Image Credit: Harvard’s Wyss Institute