New Medical Device Coating Prevents Blood Clots, Repels Bacteria

By Chuck Seegert, Ph.D.

Implantable medical devices have always been challenged by blood clots and bacterial infection. Now, a new surface coating developed by Harvard researchers could solve both of those problems — using materials already approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

Bodily reactions to implants can be complex and even threaten the stability and success of an implant. Formation of blood clots that are activated by the surface of the implanted biomaterial can lead to the closure of catheters, unless they are treated regularly. Usually they are treated with anticoagulants like heparin, which has its own drawbacks. Additionally, implants can be the site of infection, as bacteria adhere to them and proliferate.

Getting away from the need for anticoagulants was the driving force for a research program at Harvard University.

"Devising a way to prevent blood clotting without using anticoagulants is one of the holy grails in medicine," said Don Ingber, M.D., Ph.D., the Founding Director of Harvard's Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering and senior author of the study, in a recent press release.

The idea for the new technology, which is called Slippery Liquid-Infused Porous Surfaces (SLIPS), was inspired by nature and the abilities of the pitcher plant, a carnivorous species that eats bugs, according to the press release. SLIPS is capable of repelling virtually any material, due to the liquid layer on its surface.

The adaptation of the natural surface to medical devices involved a two-step process whereby a chemically attached monolayer of perfluorcarbon was added to the surface of the device. Liquid perfluorocarbon, a material similar to Teflon, was then added and kept at the surface of the device by the attached monolayer.

Testing this process on over 20 different biomaterials showed that the process could be used on a wide variety of surfaces, according to the press release. When the surfaces of arteriovenous shunts were implanted into pigs, the surface prevented blood clots from forming for a duration of eight hours, according to a study the team published in Nature Biotechnology.

"We were wonderfully surprised by how well the TLP [Tethered–Liquid Perfluorocarbon] coating worked, particularly in vivo without heparin," said one of the co-lead authors, Anna Waterhouse, Ph.D., a Wyss Institute Postdoctoral Fellow, in the press release. "Usually the blood will start to clot within an hour in the extracorporeal circuit, so our experiments really demonstrate the clinical relevance of this new coating."

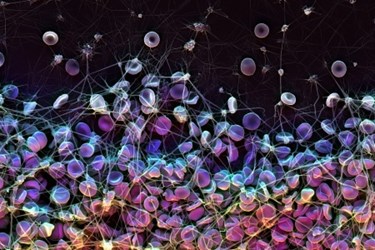

Image Credit: Harvard's Wyss Institute