New Device Coating Protects Against Bacteria, Fungus, and Yeast Infections

A team of French scientists are developing an ultra-thin, multi-layer device surface coating that is effective against the infections most commonly known to cause implant rejection, even those resistant to antibiotics. Researchers say the different layers ensure the coating is long-lasting and capable of controlling inflammation and resisting multiple types of pathogens.

A study published in Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases estimated that five percent of all surgical implants become infected, and these complications can lead to costly and painful revision surgeries, as well as prolonged hospital stays. While considerable effort has been made to address these risks, researchers are still looking for ways to make implants safer, especially with antibiotic-resistant bacteria strains on the rise.

One approach has been to develop implants with anti-microbial features built into their design. A team from Harvard recently introduced a self-replenishing, oily coating that discourages bacteria from colonizing on a device’s surface. Other researchers, such as a team from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University, are developing implants that dissolve over time, mitigating the risk of an infection occurring down the road.

While coating implants with antibiotics prior to surgery has reduced risk, researchers say that emerging strains of bacteria restrict coatings’ effectiveness. A team from the French Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM) believes that a multi-layered approach could offer more comprehensive protection from a variety of different threats.

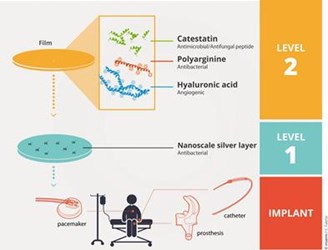

According to a study published in Advanced Healthcare Materials, the film is between 400-600 nanometers thick — practically invisible to the naked eye — and uses four key substances: polyarginine (PAR), hyaluronic acid (HA), antimicrobial peptides, and silver. The PAR controls inflammatory response, and the HA works to inhibit bacterial growth. The peptides, catestatin in particular, work as an alternative to antibiotics, killing off bacteria.

In a YouTube video explaining the design, INSERM biochemist and biophysicist Philippe Lavalle explained that the anti-microbial agents are contained in polymer layer that begins to degrade as soon as the implant is placed, releasing the agents almost immediately and putting them to work.

“This is very important,” said Lavalle, “since we know that the first few hours are critical when inserting biomaterial, as that is when we must fight against chronic inflammatory and infectious processes. Our coating is effective against yeast, fungal infections, and bacterial infections such as Staphylococcus aureus, which is known to be resistant to antibiotics.”

All of the elements together, said Lavalle in a press release, last about 24 hours in the system. To prolong the anti-microbial activity, the scientists included a layer of silver, a known anti-infectious material that is currently used in catheters and dressings.

Lavalle added that the coating is currently being tested in heart valve implants placed in rats, but he imagines it could be available within the next few years for devices frequently prone to infection, such as catheters, orthopedic implants, and pacemakers.