How Will Conducting A Medical Device Clinical Trial Outside The U.S. Impact Your FDA Approval?

By Janice Hogan, Partner and Co-Director of the FDA/Medical Device Practice, Hogan Lovells US LLP

The rapidly increasing cost of clinical research has led to growing interest in cost-saving strategies. A 2012 report by Kramer and Schulman indicated that the cost of clinical research has exceeded inflation by 7.4 percent annually for the last 20 years.1 Given this trajectory, manufacturers of medical products have pursued a number of options to reduce cost, including the use of data from sites outside the United States.

Depending on the site and the cost of care in that location, a clinical study conducted outside the U.S. can result in savings of 30 to 50 percent or more, compared to the cost of corresponding research in the U.S. Given the estimated cost of medical device clinical trials to support approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which ranges from $1 million to $10 million or more, the use of foreign clinical data can produce meaningful savings.

In addition to providing direct cost savings, the use of foreign clinical data to support FDA submissions can be a time-saver. Reduced time to market can have an even more profound impact on total investment than direct cost savings, particularly for startup companies. For example, time savings can result if foreign clinical studies can be initiated earlier than corresponding U.S. studies. In the U.S., studies that present "significant risk" to human subjects require prior FDA approval of an investigational device exemption (IDE) application,2 as well as local institutional review board (IRB) approval. By comparison, for products that obtain CE marking prior to FDA approval, the process of initiating post-CE mark studies may be significantly more expeditious than obtaining IDE approval.

In an effort to address this issue, both Congress and the FDA have taken steps to improve the process for initiating U.S. clinical research. Under the Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act of 2012 (FDASIA), the IDE approval provisions were revised to permit IDE disapproval only if a study was deemed unsafe.3 Previously, the FDA could deny IDE approval even if a study was safe, if the FDA considered the study design unacceptable or not statistically robust. The purpose of this change was to increase the rate of first round IDE approvals, thereby decreasing industry motivation to "offshore" clinical research. The FDA also implemented new programs for early feasibility studies, another effort to improve the regulatory climate for U.S. clinical research.4 Although there is limited data to assess whether these changes have been effective, there is some preliminary evidence to suggest that IDE approvals are accelerating.

Still, FDA efforts to improve the IDE approval process cannot address the underlying cost differential between U.S. and foreign clinical studies. Califf et al. have reported the relative cost of performing clinical trials in the U.S. is approximately twice the cost of performing studies outside of the U.S.

Therefore, manufacturers are likely to continue considering use of foreign data as partial or complete support for FDA submissions. This article examines the impact of this cost-saving strategy on the FDA review and approval process.

FDA Framework For Use Of Foreign Data In Medical Device Submissions

The FDA generally recognized that foreign clinical studies should be acceptable to support product clearance if they are conducted in a robust manner with appropriate informed consent and ethical oversight; are applicable to the U.S. population; and are representative of U.S. medical practice. These principles regarding the use of foreign clinical data in FDA submissions are addressed in applicable FDA regulations, such as the premarket approval (PMA) regulation.5 FDASIA also reinforced the acceptance of foreign clinical data: Section 1123 of FDASIA requires the FDA to accept data from clinical investigations conducted outside the United States if the data meets applicable FDA standards.6 If the FDA concludes that the foreign data is not acceptable, a written notice must be provided to the sponsor, outlining the agency's rationale.

Furthermore, in April 2015, the FDA issued a new draft guidance document, Acceptance of Medical Device Clinical Data from Studies Conducted Outside the United States.7 The guidance recognizes the likelihood of increasing use of foreign data in the future, stating: "The number of IDE applications and submissions for marketing authorization supported by OUS clinical trials has increased in recent years and will likely continue to increase in the future."8 The guidance reiterates the general principles regarding acceptance of foreign data described above, but it also provides examples of successful and unsuccessful uses of foreign data in prior submissions. The FDA also has issued a proposed rule, not yet finalized, that would require foreign clinical data in all premarket submissions to comply with Good Clinical Practices (GCPs).9

Despite the existing framework for acceptance of foreign data, as reinforced by FDASIA and recent FDA guidance, medical device manufacturers often must weigh the advantages of foreign studies against the potential disadvantages. First, whether it is perception or reality, many manufacturers feel that the FDA has at least an unspoken preference for some U.S.-based data collection. Second, a foreign clinical study may be more difficult for a U.S. sponsor to oversee, in terms of logistics, language, monitoring, etc. Other considerations, such as future publication of the data and marketing impact, also weigh into the decision of where studies should be conducted.

Trends In The Use Of Foreign Clinical Data And Impact On Review Times

At present, it is estimated that more than half of all clinical trials are conducted outside the U.S. Over the past decade, the proportion of studies performed in the U.S. has steadily decreased. Between 2004 and 2009, the amount of U.S.-based clinical trials listed on ClinicalTrials.gov decreased from 78.7 percent to 45 percent. U.S.-based clinical trials for medical technology products, specifically, dropped from 86.9 percent to 44.8 percent during the same period.10

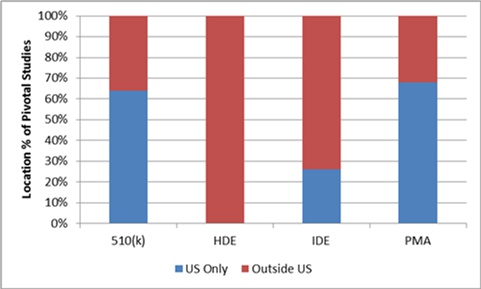

In 2013, the FDA reported that the proportion of submissions for medical devices using foreign clinical data, in whole or in part, was approximately 32 percent for PMA applications and 36 percent for 510(k) notices.11 Three-quarters of IDE applications (74 percent) and 100 percent of humanitarian device exemption (HDE) applications used at least some foreign clinical data (see Figure 1). The FDA report was based on a sample of submissions from 2009, which excluded diagnostic products. It should be noted that, because over 90 percent of 510(k) notices in that year did not require clinical data, the vast majority of the submissions sampled were PMA applications and IDE applications. However, there was no analysis whether the use of foreign clinical data impacted the FDA review process or overall approval times.

Figure 1: Use of foreign clinical data in medical device submissions, 2009 (any foreign data versus no foreign data)

An analysis of more current data for PMA applications, from 2012 to 2015, was performed to assess the impact of foreign clinical data on FDA review and approval times. Because publicly available information on 510(k) clearances does not always describe the nature or location of clinical studies performed to support clearance, the analysis was limited to PMA approvals.

Among a sample of approximately 100 PMA applications approved since 2012, overall mean PMA review time was about 21 months (total time from PMA submission to approval). There was substantial variability in review times, as shown in the scatter plot below. However, the use of foreign clinical data did not appear to have a significant impact.

Figure 2: PMA review time (filing to approval), 2012 to May 2015

Approximately one-fourth of the PMAs were for diagnostic products, and three-fourths were for therapeutic products.

Compared to the FDA's reported statistics on the use of foreign clinical data in 2009, the use of foreign data in PMA submissions appears to be increasing. In 2009, the FDA reported that about one-third of PMA submissions used foreign data (32 percent). For the period between 2012 and May 2015, this proportion increased to 41 percent. Approximately 45 percent of therapeutic product PMA applications and 28 percent of diagnostic PMA applications submitted during this period included foreign clinical data.

Analyzing the effect of foreign data use on review times showed no significant impact. The mean review time for PMAs that used foreign clinical data was about 17 months, compared to 23 months for PMAs that used only U.S. data. See Figure 3.

Figure 3: Mean PMA review time (filing to approval), with and without use of foreign clinical data

Discussion

While there are many factors to consider in deciding whether to use foreign clinical data to support an FDA submission, review of a relatively large sample of recent PMA applications suggests that the use of foreign data has no systematic negative impact on FDA review times. In the past, the FDA has cited the high cost of auditing foreign clinical studies (estimated at over $46,000) as a disadvantage for the agency, and, in some cases, the need for foreign inspections may cause delay in review. However, because the review times used in this analysis incorporate total time from filing to approval, the impact of any need for foreign inspections, resulting from the use of foreign data, is considered.

Because the data used for this analysis reflects only approved PMA applications, it is possible that the use of foreign clinical data could increase the risk of FDA disapproval. There is no corresponding data on the number of failed FDA submissions using foreign data. Differences between foreign and U.S. populations, or differences in medical practice, could adversely impact study success and approval. Even beyond FDA approval, reimbursement considerations may favor collection of U.S. data, at least in some instances.

Use of foreign data in FDA submissions is likely to increase in coming years, and the number of countries where clinical studies will be conducted also is likely to expand, due to increasing globalization of clinical research. While review times in aggregate do not appear to be negatively impacted by the use of foreign data, successful use of foreign data will continue to require rigorous protocol design, site selection, and monitoring. Early consultation with FDA regarding the planned use of foreign data also is important to ensuring success. Beyond simply meeting the data requirements for FDA approval, foreign studies’ pros and cons must be evaluated in the context of overall commercial needs, including publications, marketing, and reimbursement.

References

- Kramer JM, Schulman KA (2012). Transforming the Economics of Clinical Trials (Discussion Paper).

- 21 CFR Part 812.

- Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act (“FDAISA”), Pub. L. No. 112-144, § 601, 126 Stat. 1051 (2012).

- See http://www.fda.gov/downloads/medicaldevices/deviceregulationandguidance/ guidancedocuments/ucm279103.pdf

- 21 CFR Part 814.

- FDAISA, Pub. L. No. 112-144, § 1123, 126 Stat. 1113 (2012).

- http://www.fda.gov/downloads/medicaldevices/deviceregulationandguidance/ guidancedocuments/ucm443133.pdf

- Id.

- Human Subject Protection; Acceptance of Data from Clinical Studies for Medical Devices, 78 Fed. Reg. 12,664 (Feb. 25, 2013) (to be codified at 21 C.F.R. pt. 807).

- A Healthy Medical Technology Industry and a Healthy America, Testimony before the Senate Commerce Subcommittee on Competitiveness, Innovation, and Export Promotion, June 22, 2010 Stephen J. Ubl President and CEO, Advanced Medical Technology Association.

- Human Subject Protection: Acceptance of Data from Clinical Studies for Medical Devices; Proposed Rule (Docket No. FDA-2013-N-0080); Preliminary Regulatory Impact Analysis

About The Author

Janice Hogan is the managing partner of Hogan Lovells' Philadelphia office and is co-director of its FDA/Medical Device practice. Janice focuses her practice primarily on the representation of medical device, pharmaceutical, and biological product manufacturers before the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

A biomedical engineer, she held positions in marketing/marketing research for a major pharmaceutical manufacturer prior to becoming an attorney. She has authored articles regarding the medical device 510(k) review process, regulation of medical software, orphan drug regulation, and medical device products liability, and a chapter of a recent textbook, Promotion of Biomedical Products (FDLI 2006).

Janice has served as an adjunct professor at the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia and as a guest lecturer at the Wharton School, Drexel University, and Stanford University on the development and regulation of medical products. She is also a frequent lecturer at FDA regulatory law symposia and conferences on topics related to premarket approval of medical products, combination products regulation, and product development, and has served on the faculty of FDA's staff college training for new review staff.

Questions to the author may be directed to Janice.hogan@hoganlovells.com.