How To Make The Most Of Your Pre-Submission Interactions With FDA

By Michael Drues, Ph.D., President, Vascular Sciences

Without a doubt, one of the most common questions I get from medical device manufacturers is, “How early in the medical device development process should we talk to FDA?” In my 20+ years of experience bringing medical devices to market, I have found that it is never too early to talk to FDA. There are, however, several caveats to the previous statement, as I will explain.

Communication with FDA is a very broad and important topic. In fact, most delays in the medical device development process could be significantly mitigated, if not completely avoided, through more communication — and the time to start the dialog is long before making a regulatory submission. One way manufacturers can engage in earlier communication with FDA is via the Pre-Submission, or Pre-Sub, program.

Why Should You Care About Pre-Sub?

Without getting into a discussion of the relationship between engineers and regulatory professionals (which itself could be the subject of an entire article), engineering and regulatory are intimately related — as they should be. Unfortunately, in many device companies, regulatory does not get involved as early as they should, often leading to excessive delays and increased costs.

This is why it’s important to integrate your engineering and regulatory strategies from the very beginning, if possible, or at the very least as early in the process as you can. As will be discussed, the Pre-Sub process is a perfect opportunity to present both your engineering strategy and your regulatory strategy to FDA early, to obtain a ”meeting of the minds” and ensure that everyone is in agreement moving forward. Although not specifically required by regulation, I find Pre-Sub to be a prudent business practice, as I have seen the savings it yields when done effectively — and the delays and added expense created when it is overlooked.

What Pre-Sub Guidance Is Available?

To its credit, the Centers for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) has issued several guidance documents in the area of communication, the most recent being Requests for Feedback on Medical Device Submissions: The Pre-Submission Program and Meetings with Food and Drug Administration Staff (February 2014) and Types of Communication During the Review of Medical Device Submissions (April 2014). By comparison, however, the Centers for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) has released more communication guidances for drug companies than CDRH has for device companies. (Although it is beyond the scope of this article, I often consult drug and biologic guidance for ideas in dealing with medical devices and visa versa, as the underlying “regulatory logic” is the same — or at least it should be!)

In conjunction with the guidance, CDRH held a webinar on the Pre-Sub guidance shortly after its release. (You can download a video of the presentation here.) While reading the guidance and watching the webinar is a good start, it is a starting point only. As with all such resources, the guidance and webinar provide an explanation of the mechanics of the process. They say nothing about regulatory strategy or the various options, advantages, disadvantages, etc. So although this guidance adds some formality to the communication process, there is really nothing new here — some of us have been bringing devices to market using many of these practices for many years.

The Pre-Sub guidance is essentially an expansion of the pre-IDE (investigational device exemption) program, as it now includes all major medical device submission types: premarket approval (PMA), humanitarian device exemption (HDE), and premarket notification (510(k)). The guidance also includes devices regulated by the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER), e.g., in vitro diagnostics (IVDs).

IVDs are one of the fastest growing areas of medical device technology and present significant challenges to medical device manufacturers. They are regulated as medical devices under the CDRH rules, but those rules are interpreted by CBER, not CDRH. Bottom line: The way an engineer views the concept of substantial equivalence is not necessarily the same as the way a molecular biologist views it.

When Should (Or Shouldn’t) The Process Be Used?

The Pre-Sub guidance provides examples of when this process is particularly useful. My favorite example is an approach I have been taking throughout my career: When you are working on a truly new, truly novel first-of-a-kind medical device that does not have a clear regulatory pathway … yet. (For more on this topic, read my previous guest column Is Your Boring Regulatory Strategy Costing You Business?)

The vast majority of developers and reviewers are used to me-too medical devices, and there is nothing wrong with that. So if you are working on a me-too device and feel confident that you can successfully bring it to market following in the footsteps of those who went before you, then participating in the Pre-Sub program may not be a significant advantage. However, even if I am working on a me-too medical device, I still recommend presenting your plan to FDA in advance to minimize the chances of problems occurring later.

This approached was echoed recently by soon-to-be-former FDA Commissioner Margaret Hamburg when she called for “a new era of partnership” with manufacturers and greater regulatory flexibility in bringing new products to patients. “We see this model emerging where we don't just wait for an application to come to us,” Hamburg said during last year’s annual meeting of the Massachusetts Biotechnology Council. “We engage with you early and work with you throughout the development process.”

So my advice is it’s never to early — and it’s never to often — to communicate with FDA. They work for you. My goal is to have all questions addressed prior to the actual submission — that way, when the submission is made, it is essentially a “done deal,” and all that remains is for everyone to sign on the dotted line. Simply put: If there are significant questions raised after the submission, then the manufacturer has not done their job.

For those developing truly new or novel devices — or those planning to bring me-too devices to market in a different way (i.e., for a different indication and/or via a different regulatory path) — then the Pre-Sub process is definitely something to consider.

Here is a scenario I see frequently: Suppose you’re working on a new device whose classification is yet to be determined. Let’s say you’re in the grey area between Class II and Class III. You could go through the work of putting together a de novo submission (a form of down-classification) or prepare a traditional 510(k), and make your classification argument as part of your submission. In my opinion, neither regulatory strategy would be a good choice, because both carry high regulatory risk. In this context, regulatory risk means the probability that you are unsuccessful in “selling” your classification argument to FDA.

So what would be a better strategy? Separate out the classification argument from the rest of the submission. It doesn’t matter if you plan to do a de novo or a 510(k). If the FDA folks on the other side of the table do not agree that the device is “de novo-able” or “510(k)-able” (Are there such words?), than you have just wasted a bunch of time and money.

Nowhere is the regulation does it say you cannot separate out the classification argument from the rest of the submission, so why assume the regulation says something when it does not? The Pre-Sub process provides the manufacturer with a way to handle scenarios like these.

Although the Pre-Sub process can be useful in many situations, it is not for everything. The guidance lists a few examples of when this process should not be used, such as requests for clarification regarding technical guidance documents. (Although, in reality, I never ask for clarification— rather, I present a well thought-out regulatory strategy including the technology — something I do as part of any Pre-Sub meeting.

How Should The Pre-Sub Process Be Used?

It never ceases to amaze me how many people walk into FDA and essentially ask, “What should I do?” This is a terrible approach, because you are essentially opening up a Pandora’s box and have no idea what answer you will get. So, my philosophy is simple: Tell, don’t ask. Lead, don’t follow.

In a nutshell, here is the format that many of my FDA Pre-Sub presentations take: First, tell FDA what you have done thus far. Next, present the options moving forward ( option one, option two, option three, etc.) and the advantages and disadvantages of each. Finally, conclude with something like, “Based on our analysis, option two is the most appropriate, and here’s why. And oh, by the way, here are our consultants who happen to agree with us.”

And then stop talking! Don’t ask, “Do you agree?” or “Does this make sense?” Believe me, if a reviewer has a question, they will ask — that’s their job. Your job is to present and defend your plan. The reviewer’s job is to pick it apart. This process is very much like the American legal system, with the prosecution and defense. This is the way the system is designed to work.

What Is The Benefit Of Informational Meetings?

Without a doubt, my favorite type of Pre-Sub meeting is what the guidance calls an “informational meeting”, or what I affectionately refer to as a meet-and-greet. I find this type of meeting beneficial in all medical device development projects but especially in the truly new and truly novel ones.

Most device manufacturers don’t want to be the first through the door at FDA with a new device for lots of reasons, not the least of which is the unknown regulatory pathway. Me, being the contrarian I am, I love to be the first through the doors. Why? Because if I’m the second or the third or the fourth, and I want to do something differently than what was done by those before me, I now have to make the case that what the others did before was not appropriate — or perhaps even wrong — and what I propose instead is better.

The informational meeting provides a way for the manufacturer to educate the FDA about their new device, technology, technique, or whatever. The way I like to think of it is that the meet-and-greet affords me the opportunity to get the FDA to think the way I want them to think, and that is a very significant advantage. Keep competitive regulatory strategy in mind, as well.

What Are The Mechanics Of The Pre-Sub Process?

Back in the day, much of what I have described here (the meet-and-greet, for example) was accomplished informally — manufacturers and reviewers working together for the good of patients. Today, companies and governments like to have processes. The Pre-Sub guidance presents a lot of detail on the process, which I won’t get into here, because you can read it in the guidance. But let me be clear: There is really not much new here, at least in principle, because many have essentially been following these best practices for a long time without all the formalities.

Nonetheless, there are just a few points I would like to expand upon regarding the mechanics of the Pre-Sub process. First, as I alluded to at the beginning, there are many forms of communication between the manufacturer and the FDA. These, including Pre-Subs, are now collectively being referred to by FDA as “Q-Subs” and will be assigned an identification number — a Q followed by two digits for the year (I guess we didn’t learn anything with the last change of millennia!) and four digits representing the order in which it was received. If this leads to greater efficiency, terrific. If not, it’s just more red tape.

Pragmatically, one of the most useful parts of the Q-Sub guidance is Appendix 2, the Q-Sub Acceptance Checklist. This is similar to the 510(k) Refuse-to-Accept (RTA) Checklist (see Refuse to Accept Policy for 510(k)s, December 2012). The Q-Sub checklist includes many (though definitely not all) of the important sections that should be a part of any Q-Sub request.

Please keep in mind that this is only guidance, and like all guidance it is not binding. No matter what a guidance document may ask for, it is ultimately up to the manufacturer to decide what to provide and what not to. It should go without saying, however, that the manufacturer should choose its battles carefully. For example, if something is requested but not required, and it can be easily provided, it’s probably easier to simply comply and move on. On the other hand, something that would take considerable time and money to provide may be worth fighting over — politely and respectfully, of course!

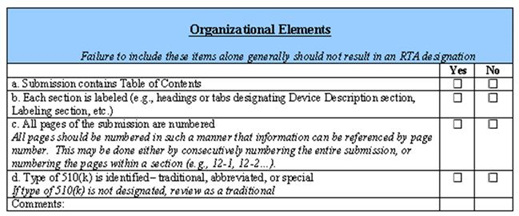

Some might ask, “Do we need such checklists?” Apparently the answer is “yes.” Consider the 510(k) RTA checklist as an example. While there are many important items on the checklist, there are also many very basic ones as well, as you can see in the screenshot of the checklist below.

With all due respect, do we need anyone, let alone our federal government, telling us to put our names on our homework assignments? Apparently we do, because approximately 60% of all newly filed 510(k)s as of September 2013 were refused under the RTA, according to CDRH. Perhaps this is an indictment of our educational system, but as responsible professionals, shouldn’t we know this already? So on one hand, I think it’s unfortunately we need such micro-management. On the other hand, the checklists exist, so we might as well use them, lest we inadvertently forget something important or trivial.

At the end of the day, if a submission is kicked back on scientific review, that’s probably legitimate — perhaps there was a disagreement with the experimental design, statistical analysis, etc., and FDA is doing their job by challenging the manufacturer (although these questions can largely be avoided by using the Pre-Sub process effectively). But if a submission is kicked back on administrative review, perhaps because a section is omitted, or worse, there are no page numbers, that is the submitter’s fault and should never happen.

Are Q-Sub Results Binding?

Another common question manufacturers ask me is, “Are the decisions made as a result of the Q-Sub process binding?” Believe me, I wish I could say yes, but in reality that’s simply not the case, but there are ways to hedge your bets. Let me illustrate by way of example…

It has been a best practice of mine, since long before the Pre-Sub guidance issued, to follow up all meet-and-greet meetings with a letter of understanding. The letter simply includes who attended the meeting, the options discussed, and how we agreed to proceed. Is such a letter binding? Of course not, but here’s why I do it anyway: I have been in situations where you come to an agreement with a reviewer on how to proceed only to find, that six months later, there is a new reviewer who does not agree with the previous reviewer. The new reviewer wants you to do more. Manufacturers get frustrated in such scenarios, and rightly so.

So here is my advice: At that point, I say “Okay Mr. or Ms. FDA reviewer, I’m happy to discuss whatever additional work you’re asking me to do.” (Please note: I am parsing my words very carefully. I am not saying I will do what the review is asking me to do. I’m simply saying I’m happy to discuss it.) Then I continue with, “But before I do, let me show you this letter of understanding based on our conversation with your predecessor, so that you can understand how we got to where we are now.” Once again, is this letter binding? No, but it does provide a stake in the ground for further discussion.

And here’s another tactic: In his book 7 Habits of Highly Successful People, Steven Covey wrote, “Seek first to understand, then to be understood.” So applying Dr. Covey’s wisdom, I will use situations like these as an opportunity to gain information. For example, before agreeing to do anything more, I will ask the reviewer why they are asking for this additional information. Perhaps there is a problem going on with a similar device that I don’t know about, a problem we would all like to avoid. In that case, the request for additional information is probably justified. But if the reviewer’s response is nothing more than, “that’s what the regulation says,” that is a poor excuse to do anything.

So although it is not binding, the letter of understanding is a tool to facilitate further dialogue, and is that not the objective of this entire process? I view the process of getting a medical device onto the market as a chess game or a poker match — and just understanding the rules of poker does not a good poker player make!

Today, the guidance introduces more formality to the process. Following the meeting or teleconference, the guidance reminds the manufacturer (I like to think of regulation as reminding rather than telling) to draft meeting minutes and submit the draft (including any PowerPoint slides) to the Document Control Center (DCC) within 15 calendar days of the teleconference or meeting. As a matter of professional courtesy, I send them to the lead reviewer as well as the other attendees.

As an aside, I have been in a few recent situations where the lead reviewer has offered to draft the meeting notes for me. I politely replied, “Thanks, but I’m sure you’re very busy, so I will draft them myself and send them to you.” Although on the surface it seems like I’m just being a nice guy (which I like to think I am!), can you guess the real reason for my response? Remember, this is a poker match.

Of course, FDA will review and edit the meeting minutes, if necessary, within 30 days of receipt. The final version will become the final record of the meeting or teleconference 15 calendar days after the applicant receives FDA’s edits. Of course, if edits are made that the manufacturer is uncomfortable with, they can submit a “meeting minutes disagreement” during the 15-day window. Such a disagreement should be filed by the sponsor as an amendment to the Q-Sub through the appropriate DCC. But once again, let me urge caution here — just like the ombudsman process for handling disputes, it is possible to win the battle but ultimately lose the war.

What’s The Risk Of Skipping Pre-Sub Communication?

Not surprisingly, some companies choose not to avail themselves of the Pre-Sub process (after all, only in limited circumstances are manufacturers required to use it) for fear that it may actually raise their regulatory burden. In fact, one of my customers believed in having absolutely no communication with FDA prior to the actual submission.

Realistically, the more common scenario is where the manufacturer completes the Pre-Sub process only to find that, in spite of their best efforts, they will have to do a bit more than they originally planned. This actually happens fairly frequently, and some may argue it is the FDA doing their job. (What does “least burdensome” mean again?) But even so, is it not better to know in advance what will need to be done and have everyone agree, so we can plan accordingly and mitigate the chances of confusion and delays after the submission is sent to FDA?

Bottom line: Many, if not most, problems can be greatly mitigated if not avoided completely with open and honest communication in advance. Simply put, the risk of not communicating is often far greater than the risk of communicating. This is the most important reason the Pre-Sub process exists.

When used effectively, the Pre-Submission system, in all it possible forms, can offer significant advantages to the manufacturer, not the least of which getting their device to market sooner. But if not managed improperly, Pre-Subs can add tremendous burden to the manufacturer by increasing the time to market. Knowing when and how not to use the Pre-Sub process is just as important as knowing when and how to use it. Remember: Tell, don’t ask. Lead, don’t follow.

For more on this topic, consider attending the webinar “FDA Pre-Sub Meetings for Medical Devices — Make The Most Of Your Opportunity” available here.