How Medtech Companies Can Reduce Costs And Increase Revenue Through Human Factors

By Natalie Abts, Genentech

By Natalie Abts and Andy Schaudt, National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare, MedStar Health

Healthcare is a more dangerous industry than most people realize. People are often surprised when they hear that medical error is the third leading cause of death in the United States1,2, especially considering our expectation that healthcare is here for our benefit. Despite numerous regulations and initiatives focusing on this problem, the magnitude of medical errors persists.

Part of the problem is that medical professionals are often forced to work with poorly designed devices and technologies that were developed without considering real-world usage. Through human factors engineering, however, medical device manufacturers have an opportunity to be a part of the solution. Incorporating human factors and user-centered design into medical device design lifecycles will help make the healthcare industry safer, while at the same time reducing overall costs and increasing revenues for the manufacturer.

Adopting Human Factors In Medical Device Development

Although the human factors scientific discipline is relatively new to healthcare, it has been used for decades in other complex industries such as aviation, surface transportation, military and defense, and nuclear power as a means of addressing the types of errors we see in healthcare today. It accomplishes this through studying how people interact with systems. Human factors engineers seek to optimize human performance by designing systems to match the cognitive and physical capabilities and limitations of users.

In healthcare, human factors takes into account all aspects of the care delivery system, including people factors (clinical personnel, non-clinical personnel, patients, patients’ families), technical factors (tools, equipment, hardware, software, processes), physical environment factors (layout, environmental conditions), and organizational factors (practices such as staffing levels and workload, organizational values).

When it comes to device design, human factors focuses on product usability, or how easily the intended user population can operate the device in the intended use environment. To develop a usable device, designers should employ a user-centered approach that focuses on the wants and needs of the end-users. This is especially important in healthcare because, unlike in many other industries, the user and the customer are not always the same person. Although a nurse or a physician may be the one using the product, hospital buyers and procurement personnel often make the purchasing decisions.

Without a focus on user needs, costly unintended consequences are likely to occur. Incorporating a user-centered approach early and often in the design process can lead to great benefits both financially and in terms of safety.

The problem with current medical device design cycles is that they often fail to incorporate the robust user-centered design approach that human factors demands. Design cycles focus more on functionality and customer — not user — needs. These actions can result in two major problems for device manufacturers: increased costs to the company and lower revenues after product launch.

The Cost(s) Of Neglecting Human Factors

Producing a new medical device is a complex process that can take many years to complete, involve many stakeholders, and require millions of dollars in funding. Although incorporating human factors into these early phases may seem like an additional expense in an already expensive endeavor, it can actually help to keep costs down if incorporated effectively.

For example, a common mistake made by manufacturers — even when attempting to incorporate a user-centered approach — is waiting until a product is almost finalized and nearly ready for market release to start conducting evaluations with end-users. When potential use problems or safety concerns arise late in this stage, making design changes can be quite costly. If user input is solicited when the device is still a prototype, it is easier to make updates and retest and validate alternative solutions without stalling the development process.

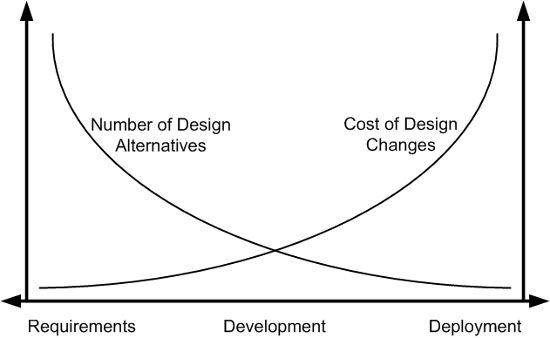

Figure 1 demonstrates how the costs of design changes can increase dramatically if not implemented in the early stages of development.

Figure 1: Cost of intervention in the product lifecycle (adapted from Bias & Mayhew, 1994)

An unusable or unsafe device continues to increase costs even after market release. One of the biggest setbacks for a manufacturer is a device recall, and usability has been a major concern leading to recalls in recent years. Approximately one-third of medical device recalls involve some sort of use error. If device issues are bad enough to cause safety problems, then costs associated with litigation become a concern as well.

Putting Revenues At Risk

Neglecting human factors may save a modest amount of money during the development process, but by doing so you fail to identify problems that may occur once the product is released. As discussed, this can cost your company money in redesigns and recalls; however, it can also lead to lost revenue due to poor user acceptance and harm to your brand.

For example, products that are complicated to use can result in poor performance and misuse that lead to adverse consequences. Hospital systems know that events causing patient harm have negative financial implications for them by raising the cost of care, increasing length of stay, and potentially resulting in costly lawsuits. They may choose to purchase competing products when replacements are needed, and negative publicity from these types of events also impacts the the manufacturer’s brand and may cause consumers to avoid purchasing other devices made by that company.

Even if design flaws don’t pose a serious safety risk, poor user satisfaction can be detrimental to future sales. If products are not well-accepted by users, hospital systems risk frequent misuse of devices, which can result in more required training, users engaging in unsafe workarounds, or decreased productivity.

Let’s look at a real-world healthcare example that demonstrates the negative effects of poor usability. Inpatient falls have been a persistent issue in healthcare that can lead to patient injury and even death. Larger hospitals can experience more than 1,000 falls per year, and the financial and emotional costs for everyone involved can be incredibly damaging.3

One of the most common strategies to mitigate this problem is the use of bed alarms, which alert the hospital staff when a patient is getting up and are often built into hospital beds. Hospital beds are a major purchase for any healthcare system and must work with many additional products and devices to be optimized. This makes usability especially important, because any design flaw can perpetuate problems throughout the product lifecycle and affect the different parts of the work system.

For example, a certain brand of hospital bed has a built-in alarm system with a poorly designed user interface that makes it difficult to determine if the bed alarm is properly activated. The primary safety issue is that inactive alarms do not alert staff to a patient exiting the bed, which may lead to a fall. With patient falls recognized as a serious and costly issue for healthcare systems, this directly increases hospital costs and can indirectly influence revenues for the manufacturer.

This isn’t the only problem the poor design creates. When nurses or technicians do not understand how to operate the device interface, they often assume the bed is broken and send it to be repaired. The maintenance staff, not knowing what the problem is, wastes time going through a checklist to make sure all aspects of the bed are functioning properly, only to send a bed that that wasn’t broken in the first place back into rotation to continue the cycle.

Add in other issues such as poor interoperability with the hospital call system (which affects the nurse’s ability to receive the alarm signals when outside of the room), reliance on inconsistent training methods to teach new employees how to operate the beds, and wasted resources from having to use portable alarms as a replacement for the “broken” bed alarms, and you have a system that is functioning unsafely and inefficiently due to the influence of one poorly designed product. All of these issues are costly to a medical device manufacturer's customer and can easily deter them from purchasing from your company in the future.

Many healthcare systems (including MedStar Health) are also starting to move towards involving usability experts to evaluate potential new products during the procurement process, and device manufacturers who have incorporated human factors in their development process will have an advantage selling into such systems.

Implementing Human Factors Throughout The Product Lifecycle

Now that you know what needs to be done, the question is, “How?” What types of activities can be carried out during design and development to can help you avoid the financial pitfalls of a device that doesn’t work for the user?

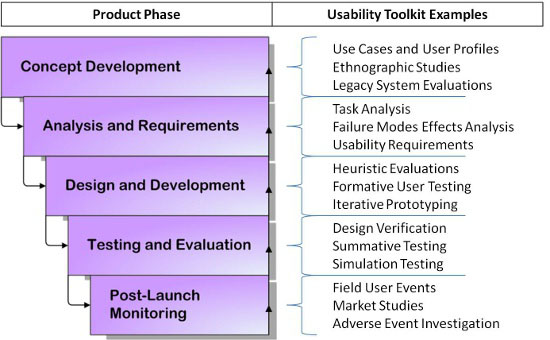

A robust approach involves usability at every stage of the product lifecycle. Figure 2 demonstrates the waterfall approach to incorporating usability consistently throughout your process. If you are still in the conceptual phase, simple tasks like end-user interviews, ethnographic observations of the working environment, and evaluation of similar currently marketed products give insight into user needs and potential areas of improvement before you become too focused one idea that may not be realistic. Once a solid concept has formed, determining which tasks will need to be performed with the device and the potential risks and consequences of errors is imperative to developing a safe product that can mitigate those risks.

Figure 2: The waterfall approach to usability in the product lifecycle

User testing assumes an important role once you hit the design and development stages. Keep in mind that user testing doesn’t have to be complex. Eighty-five percent of the usability problems with a prototype can be detected by conducting small-scale formative tests with five to six users.4 Short, iterative testing cycles during the development process makes it much easier and less expensive to make changes before a final prototype is developed.

If you’ve done your job, by the time you reach the testing and evaluation phase you will have already weeded out potentially damaging problems that could devastate revenues if not caught before market release. Even after launch, activities such as collecting usage data and exploring adverse events that occur with the device can help inform future designs and be fed back into phase one for the next device iteration.

Conclusion

At first this might sound like a lot of extra work, but many of these tasks, particularly in the early stages, can be performed by an experienced usability team for low cost and in much less time than complex, long-term clinical trials. Additionally, incorporating a user-centered approach early in the process can both reduce production costs by mitigating a redesign later in the development cycle, and increase revenue by avoiding things like recalls, complaints, and reduced sales from poor satisfaction and adverse events.

Utilizing a human factors approach to medical device design is becoming increasingly important not only for the benefit of device manufacturers and users of the device, but as a requirement during the FDA approval process. The waterfall approach to incorporating usability is a great way to maximize the benefits and avoid expensive design changes that can occur from waiting until summative stages, and the FDA will appreciate the inclusion of human factors as more than just an afterthought.

References:

- James, J.T. (2013). A New, Evidence-based Estimate of Patient Harms Associated with Hospital Care. Journal of Patient Safety, Vol. 9(3), p. 122-128.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2010). Leading causes of death. Retrieved on September 9, 2014 from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm

- Wong CA, Recktenwald AJ, Jones ML, Waterman BM, Bollini ML, Dunagan WC. The cost of serious fall-related injuries at three midwestern hospitals. Jt Commission Journal on Quality Patient Safety. 2011;37:81–7.

- Nielsen, J. (2000). Why you only need to test with 5 users. Nielsen Norman Group. Retrieved on September 11, 2014 from: http://www.nngroup.com/articles/why-you-only-need-to-test-with-5-users/

About The Authors

About The Authors

Natalie Abts is a senior human factors specialist for the National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare at the MedStar Institute for Innovation. Her work focuses on improving the design of medical devices and software through planning and executing usability studies.

Andy Schaudt is the director of usability services for the National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare at the MedStar Institute for Innovation. In this role he plans, coordinates, and manages the projects, programs, and daily operations for the usability division, which is chartered to conduct medical device and health IT usability evaluations, both for the industry and for MedStar Health (a 10-hospital healthcare system in the Washington, DC / Maryland region).

Andy Schaudt is the director of usability services for the National Center for Human Factors in Healthcare at the MedStar Institute for Innovation. In this role he plans, coordinates, and manages the projects, programs, and daily operations for the usability division, which is chartered to conduct medical device and health IT usability evaluations, both for the industry and for MedStar Health (a 10-hospital healthcare system in the Washington, DC / Maryland region).

The authors can be contacted through www.medicalhumanfactors.net.