How Dexcom Plans To Eliminate The Finger-Stick (And Bring CGM To The Masses), Part 1

By Jim Pomager, Executive Editor

Since its introduction in 2006, continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) technology has completely transformed the way diabetes is managed. CGM systems measure glucose levels in the interstitial fluid space, just below the surface of the skin. Readings are taken via a tiny titanium wire on a disposable, body-worn sensor, which transmits the data in real time to a pager-like device clipped to the belt or carried in a pocket. By delivering a steady stream of glucose measurements and, when necessary, alerts, CGM has enabled diabetes patients to correct their insulin dosing ratios and head off hyperglycemic or hypoglycemic events before they occur — in ways the traditional finger-stick never could.

And yet, the unfortunate bloodletting persists for diabetes sufferers. As things presently stand, CGM is approved only as a complement to the good, old-fashioned finger-stick, not a replacement. This is primarily due to the current generation of CGM’s accuracy, which lags slightly behind blood glucose readings in terms of precision (enough, at least, to give regulators pause). As a result, CGM users must continue to prick themselves, not only to get an “official” glucose reading, but also to calibrate their CGM systems.

Corporate and academic researchers are working feverishly to improve CGM’s accuracy and free diabetes patients from the tyranny of the finger-stick. One company that believes it is close to achieving this goal is Dexcom, a San Diego-based device maker and CGM pioneer. I recently had the pleasure of speaking with the company’s CEO, Terry Gregg, and what was intended to be a 30-minute interview quickly stretched to over an hour. We discussed the past, present, and future of Dexcom CGM technology — which was the main factor that drew him out of his retirement from Medtronic in 2005. Gregg also shared his thoughts on artificial pancreas research, the regulatory climate at FDA, potential new indications for CGM (including obesity), and a few key lessons he’s learned during decades spent in executive management at medical device companies.

What follows is the first half of that discussion. (Click here for Part 2.) Gregg’s perspective was so compelling that I decided against editing it down to our typical CEO Corner length, instead opting to publish the Q&A in (very nearly) its entirety and break it into two parts. I hope you find his insights as interesting and valuable as I did.

Med Device Online (MDO): What makes Dexcom’s CGM technology unique in the market?

Terry Gregg: Number one is its accuracy. Dexcom's CGM is the most accurate sensor in the world. Patients feel comfortable with it and trust it, to the point that it becomes part of their daily routine — part of their armamentarium of tools with which to better manage their diabetes.

Second to that is its durability. Our sensor has seven-day approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). We have, through our membrane system, figured out how to keep the immune system at bay, in terms of its reactivity to having a platinum wire inserted just beneath the surface of the skin. Our technology has achieved a much longer timeframe than anybody else has ever been able to achieve.

MDO: How did you end up joining Dexcom?

Gregg: I was, at one time, president of Medtronic Diabetes, and I knew about Dexcom. I took a team from Medtronic to visit Dexcom, to explore making a small investment in the company. (They were conducting a round of financing at the time.) Medtronic elected not to make that investment, and I elected to retire from Medtronic in 2002.

But I remained fascinated by Dexcom’s technology. At that point in time, Dexcom was focused on a fully implanted sensor that would reside in the tissue for upwards of a year before being replaced. I wasn’t convinced that sensor would be a viable product, because of the immune system and biofouling issues. But the fact that they were able to even achieve several weeks or even months in the body meant they had made great progress in overcoming what I think is the biggest challenge facing of any type of medical device — avoiding the immune system response.

I stayed in touch with Dexcom, and then I actually joined the board of directors as an independent member in 2005. By then, the company had transitioned to a short-term sensor, realizing that the long-term sensor would take too much money and time.

In 2007, the board and I decided that the current structure of the company and management team wasn’t the right one to take Dexcom to its full capability, and so I made the decision to un-retire and become CEO of the company.

MDO: So it was Dexcom’s technology that drew you to the company?

Gregg: It was really the technology, but now I’ll date myself even further. I joined MiniMed back in 1994. In 1995 or 1996, MiniMed’s R&D department had glucose sensor technology that was very rudimentary. I watched the scientists take a wire and stick it in a beaker at 100 milligrams of glucose per deciliter, then take the wire out of that beaker and stick it in another beaker at 300 milligrams per deciliter, and see the measurements read out on an instrument. For me, that was really the epiphany of what diabetes is all about. It’s the inability to control glucose levels.

So I fell in love with CGM. Although MiniMed was predominantly a pump company — and remains so today — with its continuous insulin infusion device, I always believed that CGM was more important than pumping insulin. I kept looking for a technology that would take it to the next level of sophistication, and I found that at Dexcom.

I saw in Dexcom a diamond in the rough that just needed some substantial polishing. When I joined the board, I started populating the company with people for whom I had a high degree of respect. Dexcom already had exquisite scientists and technology; they just needed to believe that we could take it to a fully commercial product. It’s been a 20-year affair with CGM, and I still, to this day, think it’s the most influential and important tool that a patient with diabetes can utilize to better manage their diabetes by better managing their glucose levels.

If you think about all the drugs that are addressing diabetes, from insulin to newer medications, they are all trying to do the same thing, and that’s to better control a patient’s glucose level. Insulin is the most dangerous drug in the world, because once it’s on board, you can’t stop it, and you have a very difficult time of controlling it. A better way to do it is to know where your glucose is all the time, to be able to titrate more properly the exact amount of insulin that you need, or carbohydrates if you need to increase your glucose level, in a more effective, efficient, convenient way for patients.

MDO: Speaking of patients, what are the most important markets for your products?

Gregg: The first category would be Type 1 diabetes patients. Next in line would be Type 2 patients, particularly those who are utilizing insulin as part of their regimen. They have exhausted their ability to sustain the effect of oral drugs, so they migrate to insulin. There are about 3.5 million Type 2 patients in the U.S. who utilize insulin.

Beyond that, there are studies that have been published indicating that Type 2 patients who are not on insulin can still benefit from continuous glucose monitoring, as a feedback mechanism to help regulate their behavior — the foods they eat, the activities they engage in (exercise), etc.

Then I would go even further. While it is not a market that we’re addressing yet, this whole world of obesity is something that we’re keen on as a future direction. Novo Nordisk is currently going through the regulatory process to get its glucose-lowering drug Victoza approved for obesity, understanding that too much glucose in somebody’s system contributes to the obesity pandemic that the world is experiencing.

Glycemic variability is something we all need to pay attention to, even individuals who do not have diabetes. Heretofore, we have always believed that if you don’t have Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes, your glucose level range stays fairly tight, but didn’t have CGM to confirm it. We only had point-of-care measurements to evaluate the glucose value at that specific point in time.

Dexcom’s CGM technology measures 288 glucose measurements every 24 hours, so now we are beginning to see glucose variability in people who don’t have diabetes. From a clinical standpoint, spikes in glucose have corresponding spikes in proinflammatory agents within the body. These contribute to some of the long-term complications typically associated with diabetes.

So we think Dexcom can be effective in a number of different ways throughout what I call the continuum of diabetes.

MDO: Will we see CGM integrated into smart watches in the next five years?

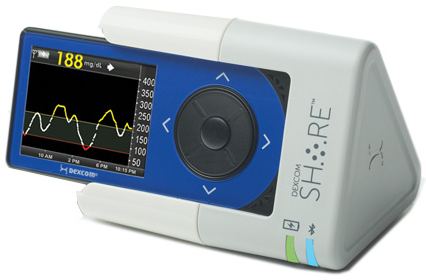

Gregg: It won’t even take five years! We have already succeeded in porting CGM information to a watch. I was on Mad Money a few months ago with Jim Cramer, and I was porting information from our Gen 5 glucose system — Gen 4 is the version currently on the market, so this was our next-generation technology — to a Pebble watch. The technology exists today, but we’re not there from a regulatory approval standpoint yet. That is why getting FDA approval for our Share system in October was so important, because it marked the first time the agency allowed active remote monitoring of glucose values, not only to the patient but also up to five followers.

It is very important for the agency to begin to get comfortable with this whole concept of connectivity, and the risks associated with that and the risk mitigations we’ve put in place, but to ultimately get that to a watch. We are working with Apple right now to integrate glucose information into their HealthKit.

We’ve got a project going on, actually, taking that information and porting it directly into a hospital system, an Epic system up at Stanford University. All of this is coming – it won’t be five years. My guess is probably in the next three years.

MDO: Please tell us more about Dexcom Share, for readers who may not be familiar with the technology.

Gregg: Dexcom Share is platform that provides the ability to share information from patient to followers. The Share system itself is a charging cradle. The patient slips the CGM receiver into the cradle, which has a Bluetooth low-energy wireless chip embedded in it. By putting an iPhone or an iPod Touch adjacent to the cradle, information from the CGM receiver is pushed up to a secure cloud server. That information can then be viewed via an app, and up to five followers can receive that information. They see a mirror of what the patient is seeing.

Share was initially intended to allow parents to monitor children within the house, but then we expanded it. What’s the biggest fear of parents who have children and adolescents with diabetes? It’s allowing their child to sleepover at a friend’s house, as an example. They have to ask the friend’s parents to monitor their child throughout the night, to ensure they don’t have a severe hypoglycemic event. Share gave parents the opportunity to feel more comfortable with allowing their children to experience a very normal thing that most kids want to do.

We are also beta testing Share with some of our employees. We employ a fairly large number of people who have Type 1 diabetes, which should not come as a surprise to anyone. Many of them travel, and the standard procedure for them when they land and get to the hotel is to call a loved one. With Share, their loved ones back home are able to monitor them from afar, whether it be next door or across the Atlantic.

That said, we ideally need to go directly from the transmitter to the phone, and bypass the Share cradle entirely. That’s one thing we are trying to achieve with our Gen 5 CGM technology.

MDO: What is your timeline for the Gen 5 product?

Gregg: We are going to file the premarket submission with the FDA in the first quarter of 2015, so I would expect a product introduction late in 2015 or early in 2016. We have certainly been in discussions with the agency for the past couple of years about this product, getting them comfortable with the concept.

This is a product that connects directly to phones, so the agency is concerned, and rightfully so, about the integrity of the signal from the transmitter to the phone. It cannot be interrupted by upgrading software, for example, or adding apps or making calls. We must always be the primary on a phone, so alerts about glucose going up or going down too rapidly can be received. That’s the kind of risk mitigation we have been working through with the FDA, as they get more comfortable with these types of devices for the future.

Connected devices are coming through the pipeline rapidly, and not only from us. As we discussed earlier, there are watches that can measure not only your heart rate, but your blood pressure, your pulse oximetry, your oxygen saturation, etc. The difference is that the type of information delivered by today’s smart watches is retrospective — it’s not really actionable. The agency is more comfortable with those.

With Share, it’s different. It has taken the game to a new level with active remote monitoring versus retrospective. That was a big hurdle to overcome with the agency, and transmitting directly to the phone will be as well.

MDO: Isn’t it somewhat ambitious to think that you might obtain a PMA for the Gen 5 in 12 months?

Gregg: Well, we have a good track record. When we introduced Gen 4, which was a brand new sensor technology, we got it through the PMA in 177 days. Gen 5 will still use the approved Gen 4 sensor technology, but with new hardware and remote connectivity.

We spend a lot of time with FDA. What we submit for Gen 5 will not be a surprise to them. Well in advance of that submission, we have sat down with them on multiple occasions and gone through every single line item to ensure that they are comfortable with it.

We have always had a very proactive regulatory relationship with the agency, telling them not only what we are doing today, but what we intend to do in the future. We are developing a Gen 6 technology that probably won’t be available until 2016 or 2017, but the FDA is well aware of the testing that has gone into it, including human feasibility testing. We strongly believe that if FDA is a partner with you, then there are no surprises on either side of the equation. That has been a very effective strategy for the company.

MDO: There has been a lot of talk in recent years about a more collaborative, more transparent CDRH. Have you found that to be the case in your dealings with the center?

Gregg: Absolutely. We’ve had Dr. Jeffrey Shuren, director of CDRH, in our office to discuss connectivity. We deal with Alberto Gutierrez and Courtney Lias from the CDRH diagnostics group. I couldn’t speak more highly of them and their interactivity with our company.

They are thoughtful. They are progressive. If you reach out to them, they are extremely receptive. Like I said, we are there at least once a month, if not twice a month, to preview technologies and seek their counsel on various subjects.

We also provide counsel to them. If you look at where Dexcom is at from a connectivity standpoint, we are much more advanced than others within the diabetes space. We employ a number of people with telecommunications backgrounds, from places like Verizon, to help us build products that work in the current infrastructure. As a result, we are able to tell the FDA — and we have been — what they should be worried about regarding connected devices. They can then use that information in a general sense, not just related to our products but all products with connectivity.

It has truly been a collaborative relationship with the agency under Dr. Shuren’s and Dr. Hamburg’s leadership. It is very proactive.