Antibiotic Thermogel To Prevent Infections In Facial Implants

A temporary implant infused with time-released antibiotic thermogel may be the key to preventing infection in patients healing from craniofacial injuries or tumor removals, according to scientists at Rice University. Their preclinical research demonstrated that the gel degrades overtime, releasing antibiotics for up to 28 days.

Severe facial injuries caused by trauma or pathological defect are typically treated with several stages of reconstructive surgery. First, the patient is implanted with a temporary spacer, which holds the bone open and allows soft surrounding tissue to heal. Later, the implant is removed and surgeons reconstruct the bones.

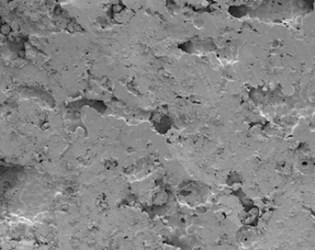

Antonio Mikos, bioengineer at Rice University, and his lab have been developing specialized plastic “space maintainers” using a material called polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) — common in facial reconstructive surgeries — to create a porous implant that can be injected with infection-fighting drugs.

“Infection is an important problem that needs to be considered with medical devices because bacteria can prevent the body from being able to heal,” said Mikos in a press release. “If the infection gets too severe, it can even cause tissues that were previously healthy to die.”

Paschalia Mountziaris, who led the researchers, noted that facial injuries were particularly susceptible to bacterial infections because of their proximity to the nasal passages, sinuses, and mouth. Mountziaris cited several studies that showed high rates of infection with facial gunshot wounds.

To reduce the rate of infections with their PMMA spacer, researchers developed a thermogel made from block polymers, which injected as a liquid but hardened to a gel when it came into contact with body heat. As the gel gradually degrades, antibiotics are released at the site of the implant to combat any potential infections that may develop in the soft tissue.

“Block copolymers can offer a lot of benefits since they are designed to take advantage of the strengths of individual polymers,” said Mikos. “The block copolymer we used for our study was designed to be able to take on water, become a gel at body temperature and slowly degrade over the course of implantation.”

The unique chemical properties of block copolymers — said the researchers — make them an ideal drug delivery platform, and scientists at Clemson University are developing time-released chemotherapy using similar principles.

In a study published in Biomedical Science, researchers tested their implant with the antibiotic colistin, which was clinically discontinued in the seventies due to its risk of renal and neurological side effects, but reintroduced recently as a last-line of defense against antimicrobial-resistant bacteria. The researchers’ in vitro studies showed that the copolymer continued to release the drug for up to 28 days.

Though the thermogel was tested with colistin, Mikos said the copolymer could be infused with other types of antibiotics, as well.

In 2013, the Department of Defense issued a $75 million grant to Rice University and the University of Texas Health and Science Center (UTHealth) to investigate novel therapeutics for regenerative medicine that could be useful to both soldiers and civilians.